Scientists at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University have discovered a new approach to water levitation, a phenomenon studied three centuries earlier by Johann Gotlob Leidenfrost. This innovative method significantly reduces the temperature at which water droplets begin to levitate above a cooled surface, which increases the efficiency of heat dissipation in water cooling systems, like those found in nuclear reactors.

Understanding the Leidenfrost Effect

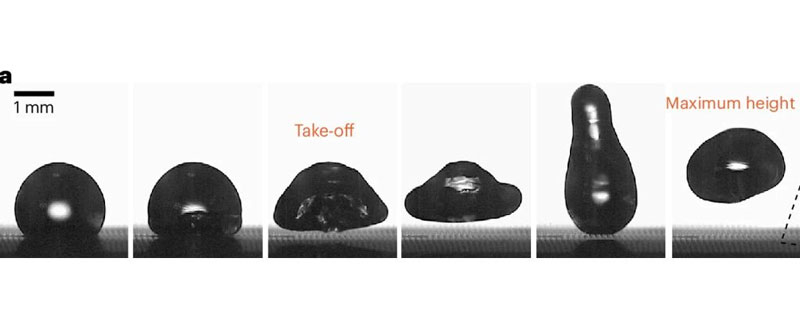

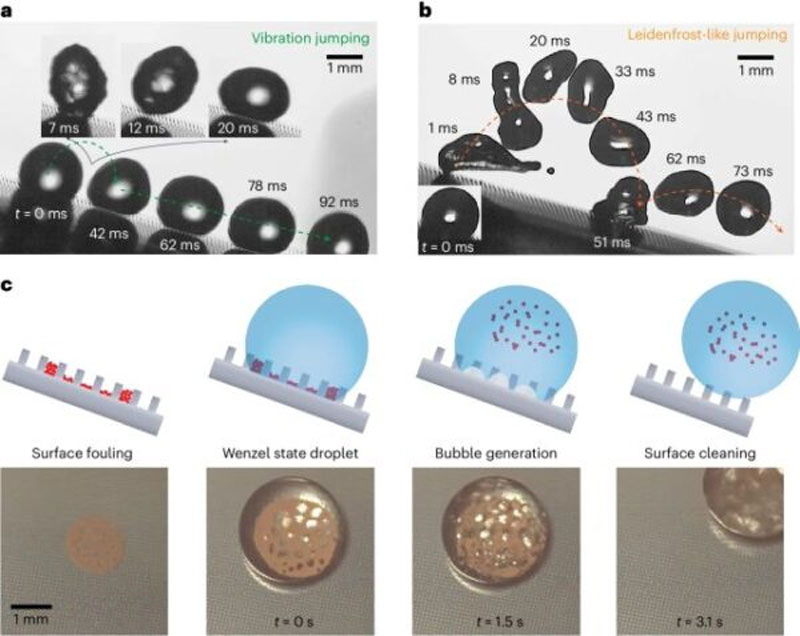

The so-called Leidenfrost Effect creates a layer of vapor between a liquid droplet and a superheated surface, acting as a thermal insulator and allowing the droplet to levitate above the surface. In critical situations, this can lead to steam explosions, which are dangerous in nuclear reactor operations and, generally, in cooling—the last thing anyone wants are surprise mishaps when operating equipment.

Researchers from Virginia aimed to create gentler conditions for heat transfer from the cooled liquid surface to decrease the risk of explosive vaporization, which increases as the medium heats up.

Exceeding Expectations

“We assumed that micropillars would alter the behavior of this well-known phenomenon [Leidenfrost Effect], but our results exceeded even our own imagination’ said Jingtao Cheng, a mechanical engineerfrom Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University ‘The observed interactions between bubbles [vapor] and droplets are a major discovery in the field of heat transfer during boiling.”

The cooled surface prepared by the scientists consists of hundreds of tiny pillars with a height of about 0.08 mm. They are arranged in a grid pattern with a cell spacing of about 0.12 mm. When placed on this surface, a drop of water covers about 100 pillars. These pillars, embedded within the droplet, accelerate boiling. Consequently, the levitation effect is significantly faster, and occurs at a lower temperature of 130 °C, instead of approximately 230 °C for regular flat surfaces.

Application Across Industries

This breakthrough could be useful in many areas that employ liquid cooling, including the field of computers and especially supercomputers, which are increasingly being located at nuclear power stations due to their rising power consumption.